Inside the family court, where justice and trauma collide

Illustration: Sophia Checkley

“I would have stayed if I’d have realised he could’ve done this to us. Because I could have protected my son better if I was there. Now I feel like I can’t protect him at all.”

Rebecca*, who lives in Bristol, left her partner after years of his behaviour becoming, she said, increasingly controlling and violent.

She took their young child with her.

Within months, her ex-partner had begun legal proceedings to have the child live with him despite, Rebecca claims, reports from children’s services and the police that corroborate her story.

This began a three-year ordeal for Rebecca fighting not only her ex-partner but also a system she believes was set up to see her fail. “Leaving was easy in comparison to this,” she said.

Rebecca became one of thousands of people each year who pass through the family court, which deals with issues such as deciding who a child lives with when their parents separate.

It does this through child arrangement orders which detail things like which parent has the child, on which days, and for how long.

Bristol family court sits inside the Civil Justice Centre in Redcliffe. It was here that Rebecca‘s story culminated in a four-hour hearing, which she described as “possibly the most traumatic experience of my life”.

Despite her barrister becoming ill shortly before the hearing, the judge refused an adjournment. Rebecca, unable to secure alternative representation, was forced to represent herself against her ex-partner and his barrister.

Her partner won the right to look after the child 50% of the time.

‘A playground for abusers’

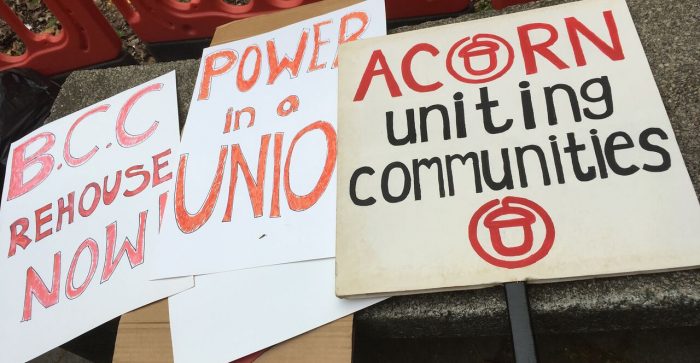

On Thursday, November 3, Hold Up Your Hands, a collective of women with experience in the family court, will stage a protest outside the Civil Justice Centre. The protest marks Family Court Awareness Month, a movement started in the US to call attention to and criticise the family court.

Hold Up Your Hands also protested outside the Bristol court back in July. At the time, one of the protesters described the family court as being a “playground for abusers”.

Domestic abuse features in 62% of family court cases, according to research by Adrienne Barnet, a senior lecturer in law at Brunel University, London, and former barrister.

But according to Barnett, the family court doesn’t fully understand domestic abuse and too often takes an overly narrow view, seeing it as comparable to incidents of assault, rather than as patterns of controlling or coercive behaviour.

“Anyone that’s not been in the family court system would presume that perpetrators of domestic abuse are held to account – but that just doesn’t happen.”

This is in contrast to how domestic abuse is treated in criminal and civil courts where, Barnett said, understanding of domestic abuse is much better, in part thanks to the Domestic Abuse Act 2021 and accompanying statutory guidance. The guidance make clear that abuse relates to patterns of behaviour rather than specific incidents, and recognises children as victims of abuse if they see, hear or experience the effects of the abuse.

Barnett said that if the law were applied correctly in the family court there would be no issue. “Unfortunately,” she says, “it’s not.”

“It’s not a system that was set up to work with trauma,” adds Ursula Lindenberg, founder and director of Voices, a Bath-based charity supporting victims and survivors of domestic abuse. Lindenberg says she has seen cases of women being served court papers while still in domestic abuse refuges.

Family court, according to Lindenberg, can be the “biggest hurdle to victims’ [and] survivors’ recovery – not only because it prolongs the challenges for those people but [because] in many cases the people are re-traumatised by that system.”

When Rebecca brought her allegations of domestic abuse against her ex-partner, she says they were dismissed and played down.

In this she is not alone. Research by Barnett found that when determining contact arrangements many judges and legal professionals disregarded claims of domestic abuse except in the most extreme circumstances, with ‘one-off’ and ‘historic’ instances believed to be irrelevant.

The domestic abuse statutory guidance notes complaints of a “systemic minimisation of allegations of domestic abuse” within the family courts. It goes on to detail steps by which to address this minimisation, such as preventing perpetrators of abuse from cross-examining their victims in family court, and stricter application of existing directions for judges, barristers and court staff to respect victims of abuse in the court.

The guidance took effect in July this year – too late for Rebecca, who was left feeling abandoned by the court. “Anyone that’s not been in the family court system would just presume that perpetrators of domestic abuse are held to account and they’re criminalised, they’re arrested and charged and all these things,” she says. “But that just doesn’t happen.”

Contact at all costs

The family court performs a very difficult job dealing with highly complex situations of family separation. Of the quarter of a million cases the court hears each year, many pass through the process smoothly. However, there are others, like Rebecca’s, where the process breaks down.

In her research, Barnett reports that of family court cases where domestic abuse was alleged against a parent, 40% result in direct, unsupervised contact of the child with that parent. No contact orders, which would prevent a parent seeing their child at all, were made in less than 2% of cases.

To understand why, it is important to understand the competing principles at the heart of the family court.

On the one hand the court employs a children-first approach, taking as a paramount consideration the child’s best interest, in line with the 1989 Children Act. But how, asks Barnett, “is a court supposed to determine what is in the best interest of a child?” She argues that the court’s interpretation of a child’s best interest is framed by wider social and political attitudes.

Since the 1980s, says Barnett, courts have considered it “absolutely imperative” for children to maintain contact with both parents following separation, resulting in a ‘contact at all costs’ culture where parenthood is seen as more important than all else, including domestic abuse. She says there is no research consensus that contact always serves the best interest of the child.

According to Lindenberg, this mindset leads to a paradox. Before separation, a non-abusive parent is expected to safeguard their child and could even be told they may lose the child if they fail to leave the abuser. After separation the same court and social care system may tell the victim that failure to facilitate contact could result in loss of the child.

“The competing logics in this situation set people up to fail,” says Lindenberg. “I would say they set the non-abusive parents up to fail, and they set professionals up to fail.”

‘The 18-year sentence’

Tanya*, also from Bristol, is preparing to fight her ex-partner over whether their teenage child will live with her. The child, who Tanya fears is at serious risk of abuse, has made clear that they do not want contact with the father and, Tanya says, is regularly left shaken and mentally unwell following contact.

Like Rebecca, Tanya is being dragged into court by her ex-partner, who, she says, uses his greater wealth to bring cases and pay barristers. Tanya has a good income, but says she has still had to take out a loan and borrow money from her family to foot a bill she expects will be over £100,000.

Tanya has also been subjected by her partner to accusations of parental alienation, a highly disputed idea defined as one parent’s attempts to manipulate their children into rejecting the other parent.

Heavy criticism of the idea by clinical experts has not stopped parental alienation being widely used in family court. If taken seriously, alienation allegations can result in children being forcibly removed from the alienating parent.

When Tanya’s ex-partner tried to contact their child, in breach of a court order, Tanya was told by her own solicitor that should her child express fears about the father, Tanya’s response should be to dismiss those fears and instead tell the child the father is no threat. Anything else could be seen as evidence of alienation of the father.

A US study by domestic violence lawyer Joan S. Meier found that a father’s claims of parental alienation give him a 43% chance of winning care of the child, even when the mother’s abuse claims are credited by the court.

The domestic abuse statutory guidance excludes explicit reference to parental alienation due to the dispute over its definition. The guidance does, however, warn that abusers may seek to use the courts to continue abuse and “to manipulate children’s feelings towards [an] ex-partner.”

Emma Katz, a senior lecturer in childhood and youth at Liverpool Hope University, and an expert in domestic abuse, says accusing a partner of alienation fits with the psychology of abusers. Blaming an ex-partner for a child not wanting contact “works so well with a perpetrator’s psychology,” says Katz, “because they never want to admit that they’ve done anything wrong”.

For Tanya, her court case is dragging out the already traumatic process of leaving her abusive partner. She says the courts “have no consideration for victims of abuse and the fact they are having to live with their abusers long past their relationship ending”.

Katz calls this the “18-year sentence,” by which victims of domestic abuse are forced by court order to continue to see and come into contact with their abuser to facilitate contact between the abuser and the child.

“It can be really deleterious in so many ways,” says Katz, as children don’t necessarily understand why they have to continue seeing an abusive parent, nor that the non-abusive parent could be held in contempt of court for failing to ensure such contact.

“It can undermine the child’s feeling that the mother is there for them because she keeps having to send them into this dangerous situation,” adds Katz.

Bringing transparency to the courts

Reporting restrictions limit what journalists can communicate to the public about family court cases.

While such privacy is important to protect the anonymity of children in family court proceedings, it can also mean that if the process fails parents, as Rebecca and Tanya feel they have been failed, they are left unable to tell their stories.

“Any system where there is a high level of secrecy and a high proportion of people in vulnerable situations…is likely to have high potential for abuse,” Lindenberg says.

Efforts are being made to open the workings of the family court to public scrutiny, including by the Nuffield Family Justice Observatory, and the Transparency Project, a charity founded by lawyers and journalists that seeks to improve understanding of the court and what can be reported by journalists.

president of the family court

Partly in response to pressure from such groups, family court president Sir Andrew McFarlane published in August 2022 the results of a review into the balance between confidentiality and transparency in the family courts.

McFarlane made recommendations for greater transparency in the family court, including a loosening of restrictions on journalists attending and reporting from the family court, an increase in published judgements, greater data collection on decisions made and the consequences of those decisions, and court listings being made available to journalists.

These reforms are overseen by a newly established Transparency Implementation Group, whose work is available via a website launched in September.

Undoubtedly the family court carries out an incredibly complex job, and in cases of acrimonious family separation it may be impossible to please everyone. Yet the stories of women like Rebecca and Tanya point to deeper flaws in the court system where allegations of domestic abuse are ignored, belittled and dismissed and potential abusers face little accountability.

Hold Up Your Hands will protest outside Bristol Civil Justice Centre, 2 Redcliffe Street, from 12pm on Thursday 3 November.

Report a comment. Comments are moderated according to our Comment Policy.

Horribly one-sided account. Yes it is true that Family Court is broken and doesn’t protect children from abusers. BUT as an innocent loving non-abusive father, I can assure you it is even worse for men in this situation. The number of abusive women would shock most people not going through what I’m going through. I know lots of abused dads now. We are going through hell fighting abusive exes. Get your story straight.

its men who face this horrible torture please lets not forget that!