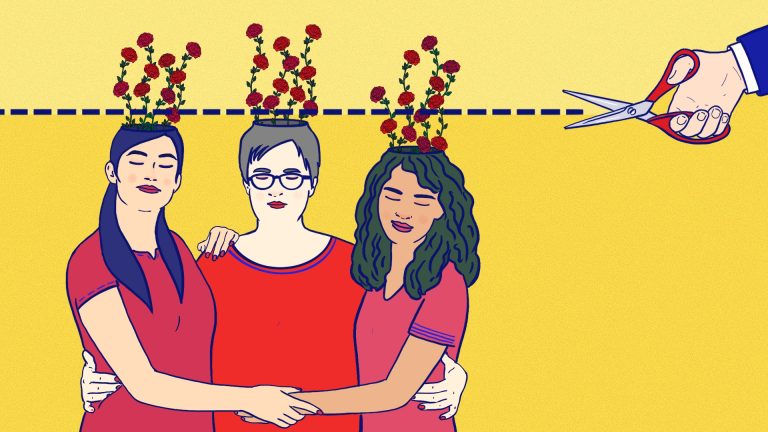

‘I needed therapy after I gave birth, but now I’m going it alone’

Photo: Aphra Evans

Warning: Contains descriptions of severe mental ill health

The phone rang as I sat on my hospital bed, still bleeding from birth, terrified of the brand new baby lying next to me in his perspex crib.

“I’d like to arrange a video call with you to see how we can help,” said the kind voice of the mental health nurse on the line.

I’d given birth two days earlier, after being admitted to hospital to induce labour due to a psychiatric breakdown. Pregnancy was arduous and painful, but towards the end I started to spiral mentally.

Just shy of 38 weeks, my husband rushed me to hospital in the middle of the night. I’d woken him at 3am with my trainers laced up, screaming that I was leaving to “get the baby out”. But by the time we arrived at the maternity unit, I was almost catatonic. Midwives tried to coax me to talk as tears poured down my face. I was medicated and prepared for induction the next day.

Paralysed by fear

This was my second baby. I’d suffered mental health symptoms with my first child too, but this was like nothing I’d experienced. I felt terrified. Of everything! Intrusive thoughts played on a loop in my head, leaving me paralysed by fear. I told my husband I felt as though I was going mad.

When I had my first child in 2016, there wasn’t a perinatal mental health (PMH) service in Bath where I lived. I got through that dark time with medication and my GP, but I never really processed it. This became apparent after my second child was born in 2021. Thankfully, there are now specialist NHS PMH community services everywhere in England, providing care for women from conception until 12 months postpartum.

For the first time, I felt safe enough to truly let down my guard. I don’t think I would have survived that period without their intervention

During my hospital stay I was monitored closely by a mental health midwife, who arranged a psychiatric evaluation, and for my care to be taken over in the community by the PMH service.

I was grateful, but wary. The fear of opening up to someone when you’ve just had a baby is real. A 2019 study by researchers at Kings College London found 30% of mothers withheld negative feelings about their mental health, for fear their child would be taken into care. I didn’t feel capable of being alone caring for our baby, but I still feared admitting this.

The PMH service assigned me a community psychiatric nurse, psychiatrist, and specialist nursery nurse. I also began a 12-week course of Dialectal Behavioural Therapy.

I’d had therapy in the past but I’d never trusted a therapist enough to speak openly to them.

This time was different. I was desperate.

‘The hardest thing I’ve put myself through’

I built a rapport with the team feeling safe enough, for the first time, to truly let down my guard. I don’t think I would have survived that period without their intervention.

Therapy wasn’t easy. It’s the hardest thing I’ve ever willingly put myself through. I showed up every week and talked about trauma, past and present. I was able to admit my worst thoughts and fears – and believe me, they got pretty dark. I began obsessing about the feeling that I was ‘going mad’. I couldn’t sleep because I feared I’d harm my family during the night.

In June 2022, a year after I gave birth, I was beginning to feel better. Although I wasn’t fully recovered, it was time for me to be discharged. I had completed treatment and was considered well enough to be referred back to my GP.

There’s no right time to end a therapeutic relationship. I knew it was coming and yet I still didn’t feel prepared to lose the people with whom I’d built a trusting relationship. It felt like grief.

I’ve since spoken to other professionals in an informal capacity about this, one being hormone-informed therapist Emily Holloway, who said: “Therapy, when it works, is a powerful and significant relationship. Having a space where you are truly heard can be transformative, so when that ends it may feel like grief… Therapy ends but the client’s bravery, vulnerability and strength is something that continues to grow and should be celebrated as the biggest success story.”

I hadn’t prepared for the impact such grief would have on my life.

Rationally, I understand why these relationships must end. Because how would I ever learn to cope alone if the NHS offered free indefinite support?

It’s been important to take things day by day, accepting how far I’ve come since that hospital admission. I better understand the work completed during therapy and the skills I learned. As Emily says, those skills are still valid, even without a team of people telling me so every week.

It’s been five months since I was discharged from the service. The sense of loss hasn’t disappeared altogether, but learning to appreciate the progress I’ve made is a huge step. I’d recommend therapy to everyone, because it really has changed my life for the better.