Bristol’s top family judge stepping down, to launch project to keep people out of court

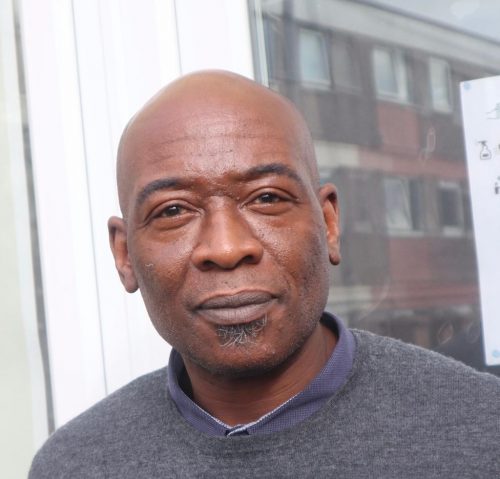

Judge Stephen Wildblood is stepping down from the family court to set up a therapeutic service (credit: @alexcarlturner)

A family court judge’s decisions can make or break a family, and have lifelong consequences. And they deliver these important decisions in private court hearings that, for the most part, are beyond public scrutiny.

Judge Stephen Wildblood presides over public law cases, which involve local authorities: making orders for adoption, and for the protection, care, and supervision of children. He also decides private law matters like divorce proceedings, financial settlements and child residence cases.

Wildblood, who is stepping down in November from his position as designated family judge for Avon, North Somerset and Gloucestershire, has a unique perspective on state intervention in family life, and how it is implemented by local authorities.

He also knows the flaws in this secretive area of our court system, and has seen firsthand how cuts to legal aid has meant that vulnerable, disadvantaged people who can’t afford to cough up thousands of pounds in fees are left to navigate the difficult and complex process alone.

This recognition and understanding of the issues with the system is a reason for him stepping back, to pursue an alternative venture aimed at supporting families before it’s necessary for the court to get involved.

In this interview to mark his exit, the 65-year-old reflects on his time in post, the weight of his responsibilities, the push for greater transparency in the family courts and the need for stronger support for families at a community level.

The revolving door

“Imagine, for a moment, a 20-year-old mother who has her every weakness, every vulnerability in her character, laid bare [in court] and used as the basis for her being told she cannot look after her child,” Wildblood says. “Her child is going to be taken away and adopted, and she’s not going to see them again.”

This (hypothetical) decision would be, quite rightly, based on what’s best for the child – their safety and protection. But what’s left for the mother, Wildblood asks, whose life will no doubt be impacted by this decision? What will she do?

“Out she goes into the community without support,” Wildblood says. “And I’ll tell you what she does: over 50% of care proceedings involve a parent who has previously had a child removed…She gets pregnant again…to compensate for the loss of her child. It’s a natural instinct.”

It must be possible to take some of these cases out of [the court] system, and so strongly do I believe in it that I’m giving up this job.

“It’s a revolving door,” he says. And now charities that support mothers who have had, or are at risk of having, their child removed are facing cuts. One of these, Pause Bristol, revealed in June that its services are not able to continue “in their current form” due to lack of funding from the city council.

“If those mothers who are not being looked after do get pregnant, of course there are going to be care proceedings, and the cost of care proceedings is huge,” Wildblood says. “Not only socially does it not make sense [to cut services] but it doesn’t make sense financially either.”

Wildblood says many of the cases he deals with involve drink, drugs, domestic abuse and mental health difficulties. “These are the sorts of cases,” he says, “where, if caught [at an early stage], a reasonable proportion ought to be capable of being diverted away from court.”

By the time a case reaches his desk, he says, chances for interventions like drug or alcohol rehabilitation have been missed.

“I do think that we ought to be doing far more to help people to find a different way of dealing with their family difficulties than going to court,” he says. “It must be possible to take some of these cases out of [the court] system, and so strongly do I believe in it that I’m giving up this job that pays me a six-figure salary.”

Wildblood, when he steps down in November, is launching a project aimed at finding a solution to family issues before they reach court. Supporting families, local authorities and other services at the “earliest stage” – “to create a structured agreement as to how the family will move forward, without the need for proceedings”.

He says the service – as yet unnamed – won’t just be open to people who can afford it. The work will largely be funded by local authorities or the parties involved, he says, in some cases when people are of limited means, where appropriate, no fee will be charged.

“What we do not want to do is set up the equivalent of a private hospital only for the rich and famous,” says Wildblood, who will work alongside consultant clinical psychologist Dr Freda Gardner on the project.

Cuts to legal aid by David Cameron’s coalition government led to, in private law cases, almost no one getting free legal help. In about 80% of private law cases at least one party does not have legal representation and, according to Ministry of Justice statistics, between January and March this year, in only 18% cases did both parties have legal representation.

Deprivation of liberty

From his bench in Bristol’s family court, Wildblood sees worrying trends in the cases that land on his desk. For instance, it was clear to him that pandemic-related lockdown measures were a “real contributor” to a spike in the number of care proceedings in recent years.

A prominent concern now, he says, is the rising number of ‘deprivation of liberty’ orders. These permit councils to impose a “secure regime” on children in settings not usually permitted under the law – and are on the rise due to a lack of secure, regulated accommodation for children with complex needs.

If a place can’t be found for them in a secure children’s home or mental health facility, councils can apply to the High Court – where Wildblood also sits – for powers to deprive the child of their liberty in an ‘unregulated placement’. This move is intended only as a last resort, but Wildblood says he might deal with as many as three cases of this kind in a day.

Wildblood says: “I either say ‘no you can’t deprive them of their liberty,’ in which case there’s a significant risk that they will be dead… or you have to say, ‘yes, fine, I will give you that authorisation’… even though that means they are going to be placed in what are called unregulated placements.”

There was a 462% increase in the number of children subject to deprivation of liberty orders in the three years to 2020/21, according to research by Nuffield Family Justice Observatory. The use of the High Court measure has been used to deprive 1,249 children of their liberty in England and Wales in the year to June 2023.

Across the country, dozens of children are being housed in unlawful facilities by local authorities because of shortages of suitable accommodation to meet complex levels of need.

A 13-year-old boy under the care of Bristol City Council was illegally sent from a privately run children’s home in the South West to live 200 miles away in a static caravan, it was revealed in October, where he is supervised around the clock by agency carers. A relative said the boy was forced to use a wash block outside the caravan due to faulty plumbing.

A corporate risk report published recently by the council revealed that between five and eight children had been housed in unlawful placements not subject to Ofsted inspections throughout the summer months of 2023. “The numbers have not reduced due to high needs of the children that have required placements, and lack of placements,” the report said.

Transparency and accountability

Wildblood’s departure from chambers comes at a time of potentially transformative reforms, in terms of transparency and accountability, to how family court cases are held.

Unlike in criminal courts, where the public can attend trials and the press can freely report on proceedings, family hearings are held behind closed doors. Only published judgements and cases where journalists have successfully applied to have reporting restrictions lifted can be reported on.

There are good reasons to keep things behind closed doors, including to protect the identity of the children involved. But holding court in private also means the process is beyond scrutiny. It also means that judges are less accountable because, providing there wasn’t an appeal, Wildblood says, “nobody would report it”.

However, a 12-month pilot project, launched in January, in Leeds, Cardiff and Carlisle, means journalists and legal bloggers can report on proceedings – providing they protect the anonymity of families involved. If successful, the changes could reach every court in England and Wales.

Wildblood acknowledges the need for this move, and praises the work of the campaigners behind it, but cautions that steps towards transparency must be taken with great care, balancing the need for openness with people’s right to privacy.

Wildblood is also trying to raise awareness about what happens behind closed doors by writing plays. “They’re not actual cases, but they are based on my experience of things that I’ve seen [in court],” he says. “I think it’s the best way of communicating the sort of difficult issues that we deal with.”

Early intervention

The human stories behind the cases Wildblood hears are often devastating. He acknowledges, with a sigh, and an apparent nod to the limitations of the judiciary, that judges do not have “magic wands” to address wider societal problems behind the cases that appear in their courtrooms.

In Wildblood’s published judgments he has rallied against a system that sees local authorities spend thousands of pounds on legal fees to argue that a mother is too unstable to bring up their child, while spending nothing on early intervention to support her to do so.

“This is an area that has affected me so much in my work that I’m saying, now, I want to go and do something about it,” he says, referring to the project he’s set to launch after stepping down. “I haven’t got that many years ahead of me, and I’m not going to waste them – I want to do something I believe in.”

Report a comment. Comments are moderated according to our Comment Policy.

About time but too late for some. How about reviewing cases of children in foster care whose family are begging for their return because they have done nothing wrong. False accusations and actions of Social Workers based on assumptions of guilt with no evidence and opinions not based on facts are rife in this tragic system.

See the stories of these on facebook. End forced adoptions and foster care facebook group.

How about then u look at my case unpick it and undo the 3 years of abuse my kids stolen by the courts and agreeing to place them back at harms way with who I left and put things right case by case I’ve lost 3 years I will never get back but do some good and work on stolen children and help get them back with the correct parent

I found this fascinating having read another article -https://www.buzzfeed.com/emilydugan/this-judge-says-he-cries-when-he-has-to-take-children-away – about this Judge. I genuinely hope that he makes progress and would be interested to hear if he has started his new venture and any details of this.

I am also keen to hear what date he stepped down as a Judge.