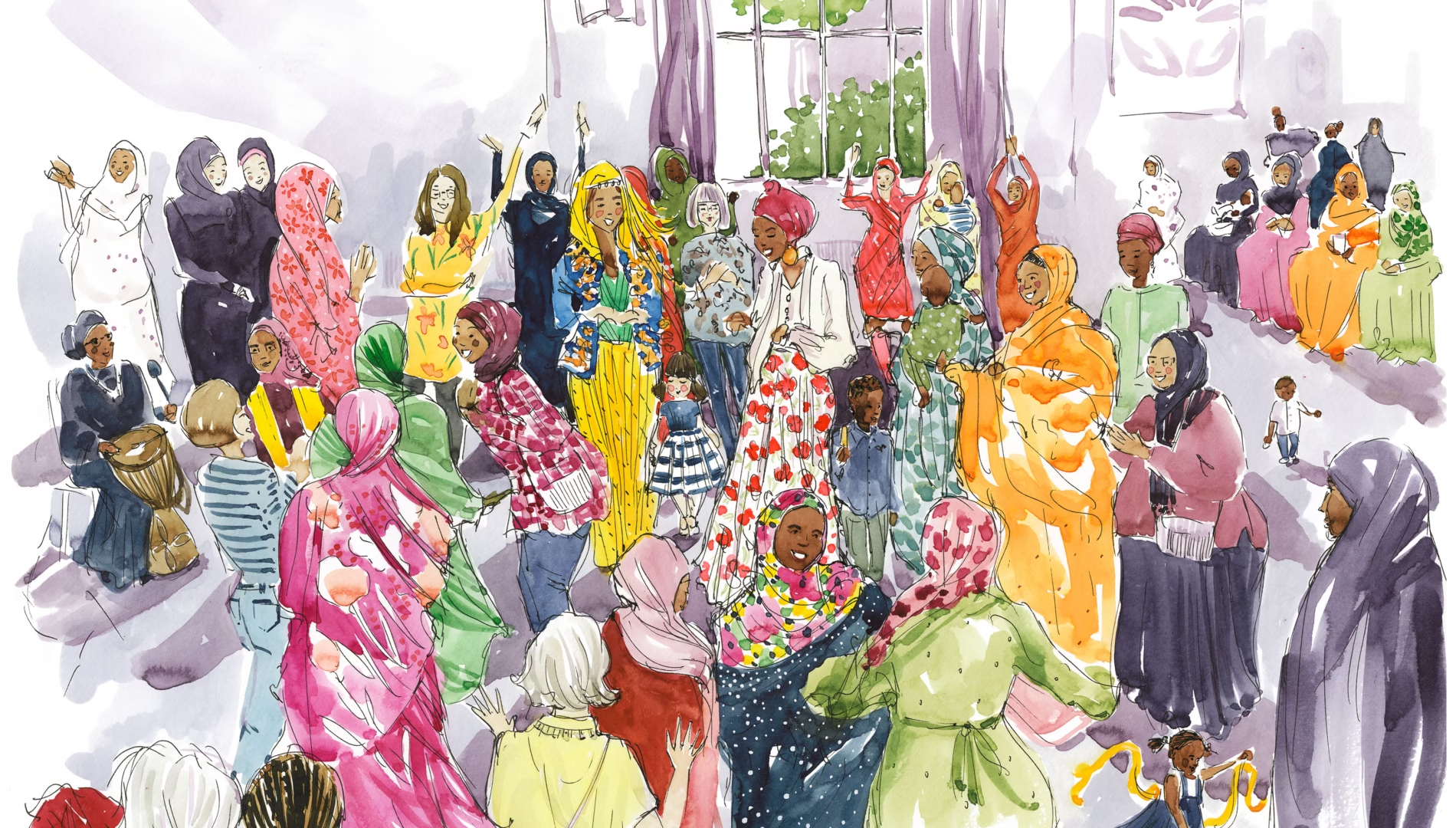

Illustration: Niki Groom

Every Tuesday, the Easton Christian Family Centre hosts a drop-in session by local charity Refugee Women of Bristol. By 11 am, the building buzzes with greetings, children heading to the crèche or tearing through corridors on tricycles.

As lunch approaches, the smell of buttery rice, cardamom, tomatoes and peppers fills the air. Cooked in big pots, the flavours the women were raised with are now shared with members and volunteers alike.

I’m one of those volunteers — and a grateful recipient of the food. I work with Citizens Advice, who offer information and guidance to anyone who needs it on welfare, bills, housing, debts or other concerns.

Refugee Women of Bristol has grown significantly since it began in 2003. Today, it’s the city’s only multi-ethnic, multi-faith organisation led by refugee women. Over 800 members represent 63 nations and speak 55 languages. Each year, it supports around 300 refugee and asylum-seeking women and their pre-school children.

It’s a vital hub — a space to share knowledge, access services, make art and build lasting friendships.

‘We can talk, even without language’

I sat outside with Aya. She first discovered the crèche during the pandemic, when her daughter was only one and a half. “Two hours a week to drink a coffee away from the children!” she laughs, gesturing to the kids climbing the frames behind us.

She tells me about her childhood in Morocco: evenings spent with the whole family stitching, beading, sewing — sharing stories as their hands worked.

Since joining the group, embroidery has helped Aya connect with people who don’t speak English, French or Arabic. “I find that we can talk, even without language.” She waves to two friends — Yemeni-Somali and Ethiopian. “You see,” she says, “when you come here, you will always find something in common.”

A few weeks ago, I joined their dance event. With their group of drummers, they created a world of music, from Kurdish folk to Afrobeat. I was marvelling at a woman in high heels, dynamically leading a dabke line, when I spotted Zahra. We’ve been working together for six months.

“Coming here is enough to change your mood!” she grinned, as we sat down to chat.

Zahra is one of millions forced to flee Sudan, where violent crime has escalated amid a war barely covered by Western media. “They’ve cut the electricity wires in Sudan,” she told me. Meeting other Sudanese women, and a whole community built on shared struggle and mutual care, has transformed her life in Bristol.

She told me about her first day — I remember it too. “I was so scared!” she said, smiling. “I didn’t know anybody here.”

“Everyone in this city is so friendly. I am very happy here. At the end of each session, I am just thinking about when next Tuesday will come!”

A hostile system, felt at home

Amidst the lively atmosphere, chatter and laughter, you’d be forgiven for forgetting the structural discrimination this community faces, as both women and migrants. Their issues — unsuitable housing, high bills, barriers to work — are worsened by a racist, hostile immigration agenda.

Asylum seekers feel the cost of living crisis acutely: stuck in substandard accommodation, often for years, banned from working, while private contractors profit. Replacing asylum hotels with proper support and granting work rights would ease pressure on councils and public services.

When you come here, you will always find something in common.

Aya

Even after leaving the asylum system, housing remains a site of injustice. The Right to Rent scheme, introduced in 2014, forces landlords to check tenants’ immigration status. Fines of up to £20,000 have led many to avoid renting to anyone without a British passport. A Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants study found that nearly half of landlords routinely refuse applicants with short-term residency rights.

One woman tells me her youngest child has developed breathing issues from the black mould spreading in her house. The extractor fan, broken for six months, still hasn’t been fixed. She’s worried the landlord might retaliate if she complains, and finding somewhere else to live feels impossible.

Stories like this are all too common: poor-quality housing, no accountability. Taking action is risky. Between an unresponsive Home Office, overstretched councils, and wary landlords, eviction and homelessness are never far away.

Foreign policy fuelling conflict

Another story that’s rarely mentioned: the factors pushing people to flee their homelands in the first place. Keir Starmer recently announced he would boost defence spending, while slashing foreign aid by 40%.

These shifting priorities show how little we’ve learnt

War and persecution force people to flee, and women disproportionately suffer. In Sudan, Afghanistan, Syria, Eritrea and Iran, countries with the highest grant-rates for asylum applications, political violence has become gendered violence.

If our foreign policy fuels conflict, of course, more people will be displaced.

But places like the Tuesday drop-in remind me that another way is possible. People meet, find joy in each other, and rebuild community in the gaps left by the state.

As co-founder and manager Layla Ismail put it: “Even a simple smile can bridge cultures. It costs nothing, but it speaks volumes.”

Independent. Investigative. Indispensable.

Investigative journalism strengthens democracy – it’s a necessity, not a luxury.

The Cable is Bristol’s independent, investigative newsroom. Owned and steered by more than 2,600 members, we produce award-winning journalism that digs deep into what’s happening in Bristol.

We are on a mission to become sustainable, and to do that we need more members. Will you help us get there?

Join the Cable today