DIY Press: From conspiracy to community coverage

Photos: Harpy, Hysteria, Womens Own & Enough reproduced with permission from The Feminist Archive, Special Collections University of Bristol

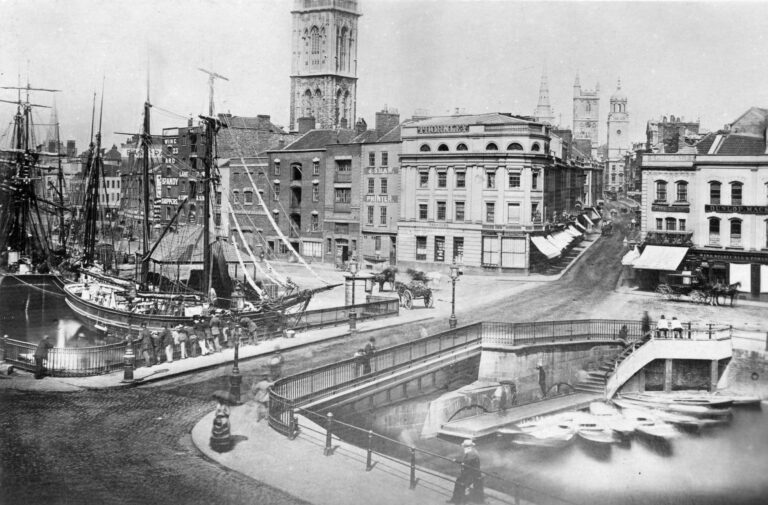

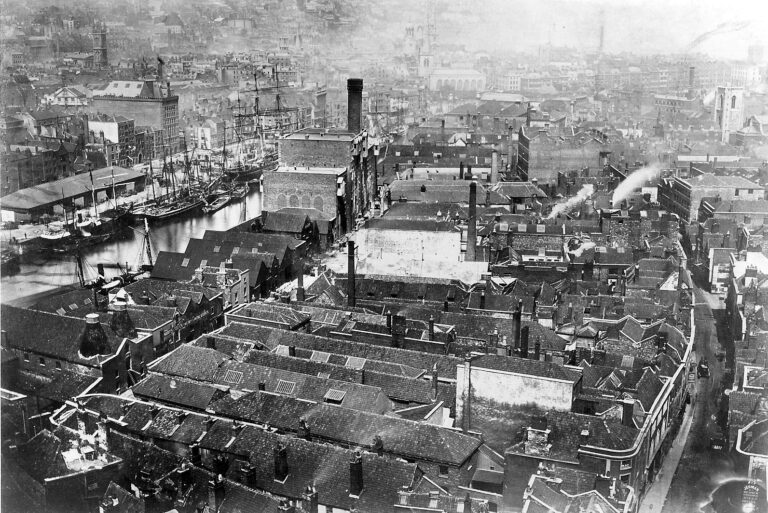

The radical papers of yesteryear are now yellowing and difficult to find. Yet a look at the tradition of alternative press in Bristol and its surroundings reveals how such fleeting and low-circulation outlets contributed to people’s democratic engagement outside mainstream politics.

The radical papers of yesteryear are now yellowing and difficult to find. Yet a look at the tradition of alternative press in Bristol and its surroundings reveals how such fleeting and low-circulation outlets contributed to people’s democratic engagement outside mainstream politics.

The revolution in radical media began in the 1960s when the technique of offset lithography (a method of printing) brought cheaper printing capacity to local grassroots groups. They created a first draft of history, written in the heat of events: a hard copy with more reliable memories than the self-conscious, wordy and distanced accounts recorded in books.

When I was a student in 1980s Bath, a Gestetner spirit duplicator printer was passed around residences, like a freaky heavyweight pet. It had to be fed on alcohol-based liquids to produce anything (like us sometimes) and could, at least in theory, print leaflets on whatever issue made the campaign frontline.

The making of radical media

The amateur, DIY ethos of radical publications produced mixed results. Alternative journals, mostly spectacular for their original art and design, could be platforms for challenging reports, critical thinking and inspired poetry or a stream of consciousness for the in-joke, the rant and conspiracy theory.

Nevertheless, they were a lively challenge to the so-called ‘objectivity’ of editors and reporters who hobnobbed with the politicians and business leaders they were supposed to hold to account. Independent community contributors saw strength in their ability to draw upon local networks to engage and represent diverse perspectives.

Through owning the means of production we saw ourselves as reclaiming a modest space for knowledge and information. In a context where student radicals dismissed the Bristol Evening Post as ‘the fascist capitalist press’, alternative publications provided outlets for challenging voices absent from corporate media. Their autonomy afforded the opportunity to prioritise issues they felt mattered most to local citizens.

Bristol Voice, for instance, described its role as ‘reporting openly on the lives and struggles of people who can’t get fair hearings in our ‘free’ press’. It became the leading paper for grassroots campaigns and resistance in the 1970s and 80s, with a track record of holding local government to account.

Former public controversies are brought back to life by flicking through the pages – such as industrial action against plant closures, council house selloffs and the St Paul’s riots.

Seeds: Bristol Street Press, published 1970-1971, was Bristol’s hippy paper. But despite its flower-power covers, Seeds dealt with issues grittily. It attacked the city’s democratic deficit, appealing to readers to fight the council’s policy of ‘murdering’ Totterdown after confrontation between locals and developers and calling out ‘democracy by the planners for the planners’. George Firsoff’s Greenleaf, meanwhile, championed the cause of travellers; frequently vilified in commercial media.

Women’s liberationist and feminist papers have included Enough in the 70s, Harpy and Hysteria in the 80s and Bellow in the 00s while local newsletters Move, Pink Parents and Gaylink covered gay issues.

Women’s liberationist and feminist papers have included Enough in the 70s, Harpy and Hysteria in the 80s and Bellow in the 00s while local newsletters Move, Pink Parents and Gaylink covered gay issues.

Of other countless local papers some outlandish titles are worth a mention for the sake of comic effect: Scrump, Glastonbury Gurner, BLAST (Bristol Lesbians Are Supremely Talented) and Evening Post Mortem. The satire of political tensions helped to capture the spirit of the times. Some may have been one-offs, now lost without trace, yet each was an experiment in production and communication.

Many publications were hyperlocals before their time, reporting on neighbourhood concerns, such as the 60s Clifton Free Press, 70s SPAM (St Pauls And Montpelier) and 90s Planet Easton.

A continuing movement

More recently, the radical press has persisted and reshaped itself. The collective behind anarchist magazine Bristle, running for two decades, switched their energies to the annual Bristol Anarchist Bookfair, leaving activist news coverage to the now defunct internet-based, self-publishing platform of Bristol Indymedia.

Still standing tall on the shoulders of past radical publications, The Bristolian, launched in 2001, seeks to seize the agenda from the mainstream press. Over the years the controversial, free satirical sheet with its motto ‘Smiter of the High and Mighty’ have published scoops and exposés of intrigues in local government and business. On its information-gathering strategy, anarchist founder Ian Bone says, “Council corruption, regeneration, property deals will get you started. Once up and running, punters will give you stories”.

The necessary tasks of challenging mainstream media’s dominance over public information and debate remain.