How St Paul’s residents fought to make the Malcolm X Centre a space for the community

Liz Jones (L) and Jagun Akinshengun at Bristol’s Malcolm X Centre (credit: @alexcarlturner)

The Malcolm X Centre in St Paul’s is a community venue renowned for its versatility – from hosting the Bristol Refugee Rights drop-in centre, to playing host to parties. But what’s less known is that the centre‘s existence today is the result of a heroic struggle by working-class Black Bristolians against austerity, racism, and police violence.

The value of community-run spaces in St Paul’s, as the area’s gentrification continues, has been made clear in recent months. On Upper York Street, racial justice charity Black South West Network has taken on the Coach House and pledged to create a “centre for Black enterprise and culture”.

Less positively, the Kuumba Centre on Hepburn Road, there has been an intensifying standoff between the committee that runs it and the council, which wants the board to vacate the building.

It’s a clash that finds an echo in the story of the Malcolm X Centre, which begins 44 years ago this month with the St Paul’s riots on 2 April 1980. Police raided the Black and White Café on Grosvenor Road, a popular meeting place for young Caribbean men, leading to what Jagun Akinshengun, the centre’s first coordinator, calls an “uprising”.

The Cable sat down with Jagun, and Liz Jones, a socialist Labour councillor for Easton in the late 80s who was in charge of the city’s community facilities, to hear more about the Malcolm X Centre’s origins. The pair built a rapport through shared struggle, and shared stories and laughs about their past allies and enemies. Despite their easy demeanour, it was evident both were formidable political firebrands in their day – who still held firm to their socialist principles.

‘Black people didn’t have a voice’

In the wake of the riots, the St Paul’s Community Association was formed in 1982. It secured funding from Avon County Council, which ran Bristol and surrounding areas before being abolished in 1986, and the Thatcher government to build a community centre on City Road. Construction began in November 1983.

“We were [socialists] – my [Jamaican] family were, so I probably have that in my DNA,” says Jagun, reflecting on his decision to get involved in the association. “Then as you come [to the UK], being Black especially, that’s the only kind of politics – you’re not going to be a full-blown capitalist”. The centre was needed because “[Black people] didn’t really have a political voice in Bristol”, he adds.

Keeping local people involved was necessary – probably that’s why politicians were even taking notice

Jagun Akinshengun

Issues with the project soon arose. The council changed the designs without adequate consultation, and building costs soared from £380,000 to £550,000, including £77,000 in “professional fees”.

Even so, keys were handed over on 17 November 1984. But major problems led to the community refusing to adopt the completed building. According to Jagun, it had been rushed through in an effort to show something was being done for the Black community.

“They built a box, and it’s supposed to be for social events and meetings – but you couldn’t use it for that because the echo in the hall was terrible,” he says, adding that you could barely have a conversation in the space, let alone play music.

There were other problems with the basement flooding, a lack of facilities and basic poor workmanship because the process had not been “worked through with the community”, Jagun adds. There was also the question of running costs, which were estimated at around £65,000 a year.

Many councillors, who lived in wealthier areas, couldn’t understand the problem, according to Liz. “They [didn’t] comprehend the different scale of things – the struggle to be able to do that.”

‘Inadequate for its purpose’

The campaign to fix the venue – then called St Barnabas Community centre – started immediately. Its chair, Ras Kuomba Balogun, is quoted in the Bristol Evening Post on 24 November 1984 as saying the association, which represented 20 St Paul’s organisations of all creeds and colours, “unanimously agree [the building] is quite inadequate for its purpose”.

The council’s response was dismissive. “We have limited resources – these people must accept this is the best we can do,” Labour councillor Bernard Chalmers, chair of the Avon community and leisure committee (before being replaced by Liz in 1986), told the Post the same month.

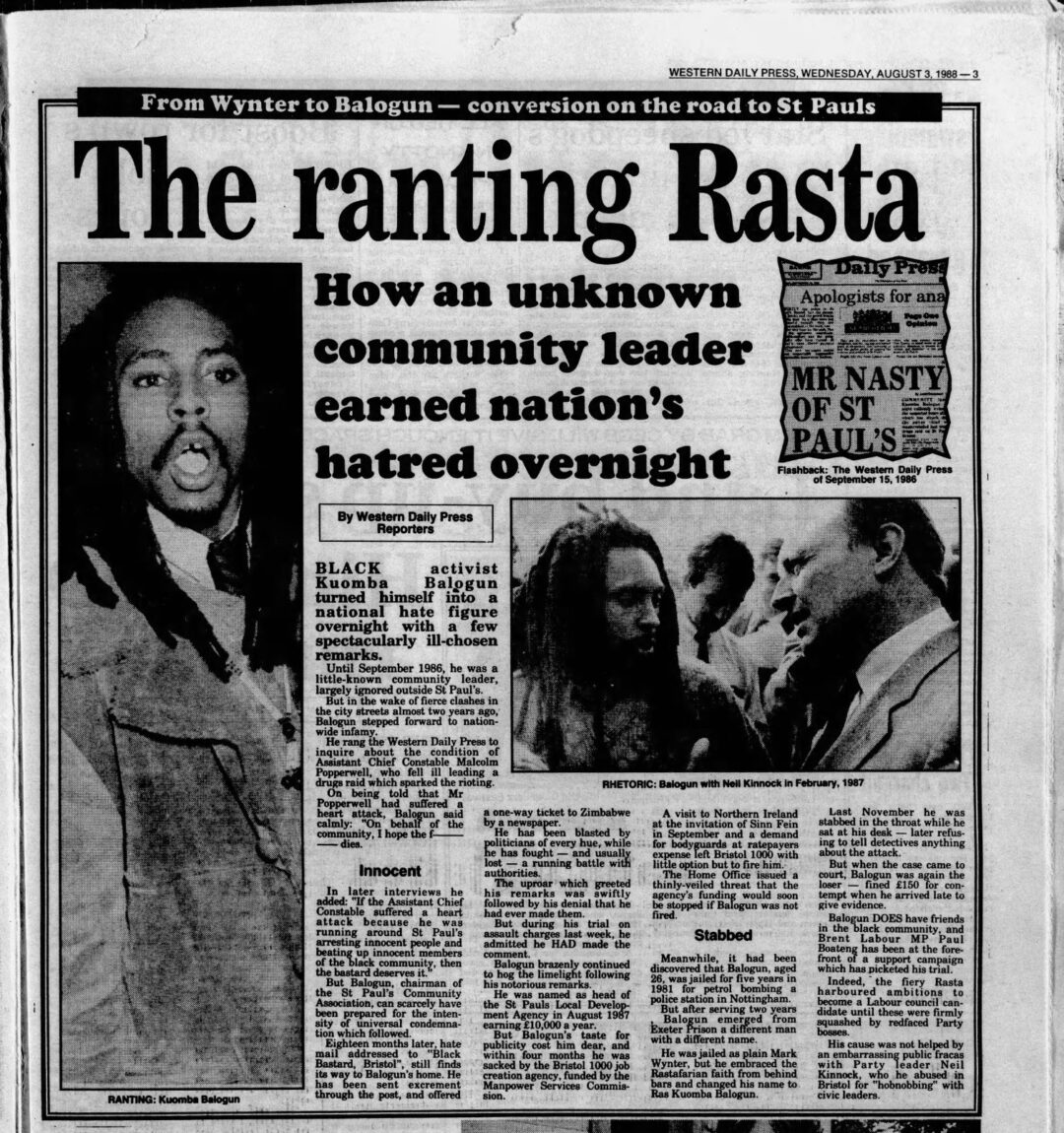

But the association remained resolute. Balogun, now known as Nana Kwaku Agyemang, was an unconventional yet passionate advocate who had converted to Rastafarianism in 1981. At the time he was in prison, after being convicted of firebombing a police station in Nottingham in retaliation to racist insults.

Balogun described the events that led to his imprisonment in a February 1985 Post article titled ‘Petrol Bomber Turned Politico’. After an altercation with the National Front, which saw neo-Nazis try to run over Balogun and his friends, they went to report the incident.

“We went to the police station to complain, and [they] told us, ‘Fuck off, you Black bastards’ – that was the attitude,” Balogun told the Post. “We were really sick about that. At some stage in your adolescence you realise there is no inlet into society for Black youth, and for me it was going to the police that night.”

The article describes how Balogun and his friends “had a whip-round, brought a gallon of petrol, and he tore up his sweater to make the whips for the Molotov cocktails”. It adds: “The rest is a small moment of criminal history.”

After serving two years of a five-year sentence Balogun moved back to Bristol, where he had grown up. He found a new purpose in the fight for the community centre.

Concerns about the space were fed back to the community through public meetings organised by the association. In December 1984, at a meeting reported on by the Post, Jagun is quoted as saying, “Some people think we should accept the building and try to make good out of bad.

“They say we ought to be grateful,” his quote continues. “We disagree… As responsible people we can in no way accept it in its current state.” The meeting, held at Cabot School, was attended by 100 people. They “unanimously decided” to refuse to take over the centre until their expectations were met.

Following the meeting, in January 1985 the association drafted 57 demands. They included addressing the flooding, adding a kitchen and changing rooms, expanding the bar, and reducing high operating costs and the issues with poor workmanship.

‘Reminding people we’re human beings’

By May, the association’s organising efforts locally, including protests to disrupt a council meeting, were making an impact. They persuaded Bristol West’s Conservative MP William Waldegrave to arrange for members to meet with Thatcher’s environment minister, Sir George Young. His ministry had part-funded the centre.

Waldegrave himself inspected the building on 10 May 1985, with the next day a community open day. “[Keeping local people involved] was necessary – probably that’s why [politicians] were even taking notice,” says Jagun.

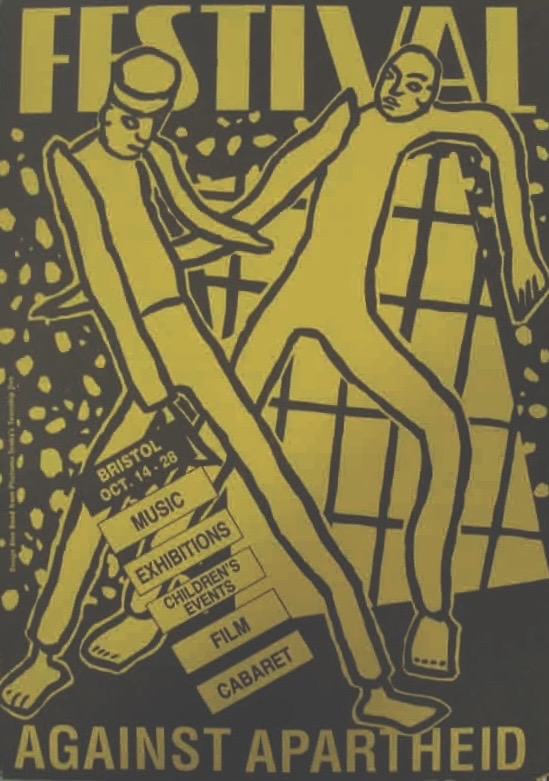

Building this power in the community went beyond the centre. Both Jagun and Balogun were also involved in organising efforts in their local Labour Party branch, as well as coordinating against South African Apartheid. They organised vigils, sit-ins in the Barclays bank branch and signed up businesses to refuse apartheid-made goods making St Paul’s an ‘Apartheid Free Zone’.

A working group to agree on funding for the centre was established, with representatives from the council, government, and the Association.

Jagun recalls how alien the meetings’ bureaucracy felt to ordinary people – but also that activists were able to push forward by not ceding ground. “[They] put us into these big rooms and tables,” he says. “We’re just community people, you know… they come in with these massive folders, and for somebody like me, that’s pretty intimidating.”

At one meeting, Liz, who had been elected as councillor on May 2, 1985, began to breastfeed her newborn. “It totally throws [other councillors] and gave us the power,” says Jagun, directing thanks to his old friend for “[reminding] everybody around the table that we’re all human beings.”

“Straight away, Balogun started to speak – and then we started to be able to talk, where before we’re trying to make our language all so official and we’re losing the point,” he goes on. “I can’t explain to you how powerful it was, Liz.”

Liz responds with typical dry humour. “It made the Evening Post that I’m feeding this baby,” she says. “Someone reported me, saying ‘It’s very off putting’. So, the Post asked me, ‘Why are you feeding the baby?’ and I said, ‘Because it was hungry.’”

Other class-conscious white allies played their part, Jagun adds. Dave Sutton, a motor-mouthed architect, helped in negotiations to overcome the “language barrier” when dealing with officials.

This approach to making allies based on class, and shared anti-imperialist politics, was further displayed by Balogun who later, in 1987, led a delegation of Black Labour Party members to meet Sinn Fein in Belfast. In a speech there he spoke of a “natural alliance with the Irish people, who have gone through the [same] process of dehumanisation” as Black communities.

External pressure

Before long though, members of the campaign began attracting pressure, including from sections of the press and Avon and Somerset Police.

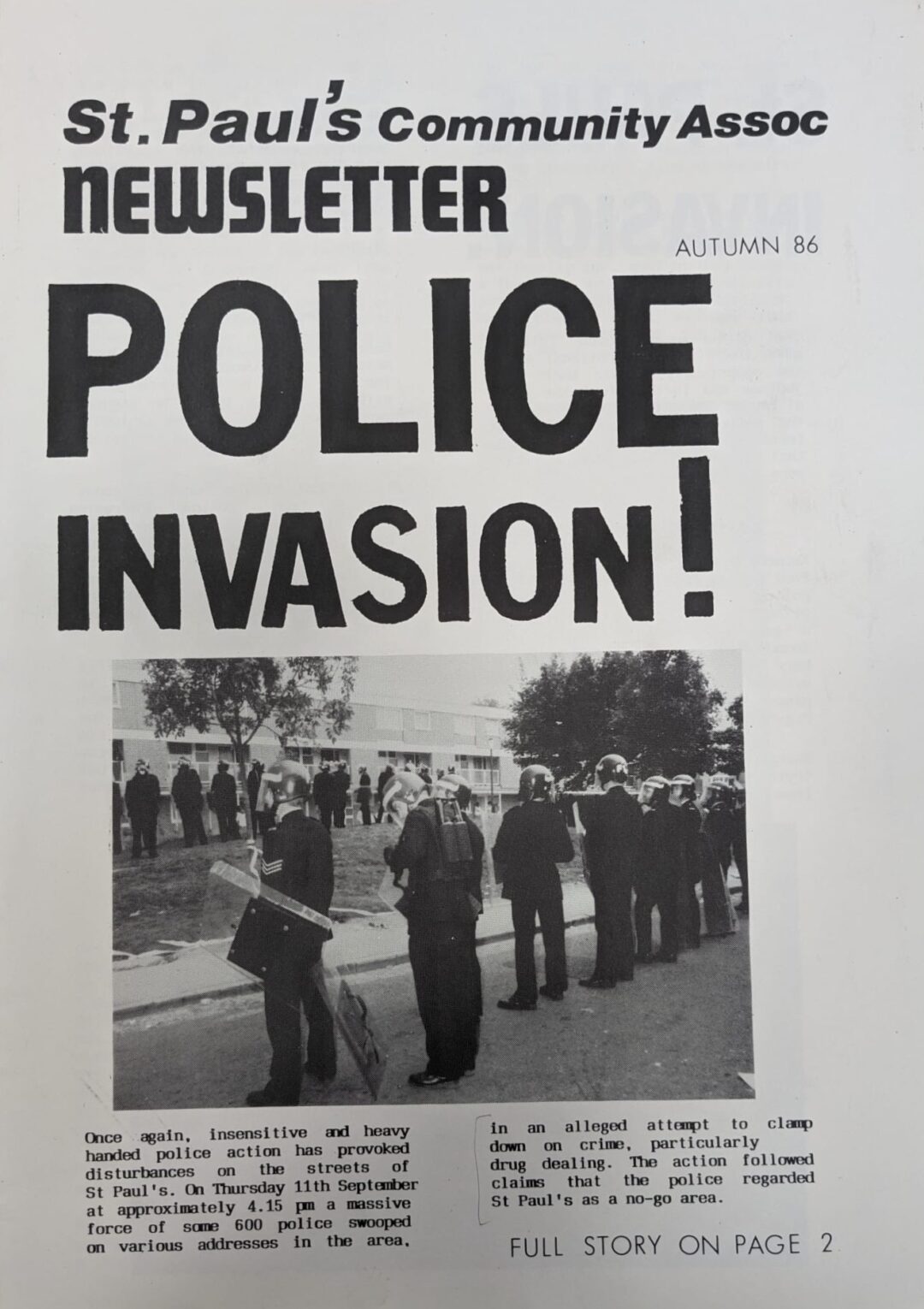

One significant event was ‘Operation Delivery’, in 1986. On 11 September, 600 officers ostensibly looking for drug dealers and weapons descended on St Paul’s.

There were more than 100 arrests – mostly of people protesting the police presence – with individuals being subjected to strip and cavity searches.

Balogun was arrested on the charge of threatening behaviour and assaulting a police officer after trying to defuse the situation, and received a six-month suspended sentence.

When asked about the operation lead, Sergeant Popperwell, who’d had a heart attack days after the operation, Balogun was quoted as saying, “On behalf of the black community, I hope the bastard dies.” The quote made national news.

Jagun attempted to defuse the situation, saying the Association “dissociate ourselves from such statements… [Popperwell] caused a lot of suffering in the community, but he is a human being”. He delivered a 10-minute speech laying out the community’s concerns during a full council debate over the operation.

The diplomacy didn’t work. In October 1986, the Western Daily Press ran a story outlining Jagun’s residential rent arrears and his compensation for his role at the association. “The usual thing [for black activists] is [being accused of] embezzlement or mismanagement of finance, that type of thing,” he says. “[The press] always go for that.”

Negotiations ground to a halt. And in April 1987, Waldegrave publicly offered the centre to any group willing to take on the responsibility and cost of running it.

Liz successfully made the case at a full council meeting to go against the government’s decision in June 1987. Councillors agreed to use £45,000 from the local authority’s resource co-ordination committee to plug the gap between what the government was offering the centre and what was required to make improvements and cover running costs. Liz told the council: “It is a total insult to the people of St Paul’s to tell them what we should be doing with the centre without consulting them first.”

Fear of violence

Victory was on the horizon. But community tensions threatened to derail it. On 5 November 1987, Balogun was attacked in his office with a machete, nearly severing his jugular.

In April 1988, he was summoned to testify about the attack. He told the court it wasn’t “in the interest of the black community” to name his attacker. But when threatened with contempt charges named Valentine Walker, the father of Bristol’s outgoing mayor, Marvin Rees.

Though Walker was found not guilty, bad blood had built between them during Walker’s time as the association’s vice-chair. Balogun claimed in court that Walker was a police informant. “[Valentine] was trying to control the centre for his own benefit,” Jagun claims. “We had some proper physical run-ins with him.”

After the attack, the fear of violence loomed over the Association. But with threats being levelled at them, they either had to report these to the cops – which they were unwilling to do – or “deal with it ourselves”.

Jagun was imprisoned for five months in March 1988 for possession of a sawn-off shotgun – although returned to his coordinator role upon release. “I found it necessary to arm myself – [there were] groups [who] would literally come and intimidate you,” he says. “In terms of the community it didn’t do me any harm, and the people who were doing the intimidating realised how serious [things had got] – so they back off.”

Three weeks after being attacked, Balogun was arrested following a raid of his 26th birthday party. This led to him appearing in court again in June 1988 charged with assaulting a police officer and possession of shotgun shells.

Despite the officer’s inability to identify him as his attacker he was found guilty of the assault and imprisoned for six months. But the firearms charge was dropped, with his lawyer raising suspicions that the shells had been planted by police.

Finally, in September 1988, a £300,000 development deal was struck with the government and council. The centre was then defiantly renamed the ‘Malcolm X Centre’. “That’s where we were at – at the time, he was our hero,” says Jagun. By late 1989, the hall finally opened to the community, hosting a children’s day as part of the citywide Bristol Festival Against Apartheid. It’s served as a vital platform for St Paul’s ever since.

The Malcolm X Centre stuck to its founding principles of being a platform from which the Black community in Bristol could engage in politics and celebrate their culture. In its first few months, it hosted political events including a Troops Out meeting with former IRA prisoner Gerry MacLochlainn of Sinn Fein and a Malcolm X reading group. The Malcolm X Centre went on to become home to the legendary after-party of the St Paul’s Carnival.

The association had shown that through determination and class-conscious organising, it was possible against all odds to win.

A Malcolm X quote still adorns the centre’s walls, and the speech it draws from speaks to the ongoing project’s motivations: “We want freedom by any means necessary.”