The new fake news: how much of a threat does AI pose to journalism?

Artem.G, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

When Hold The Front Page’s (HTFP) David Sharman received an advertising inquiry from a new local news site, there was no reason for him to be suspicious, initially.

As an established journalism trade magazine, HTFP not only carries news stories about the industry but is also a hub for industry jobs and directory listings.

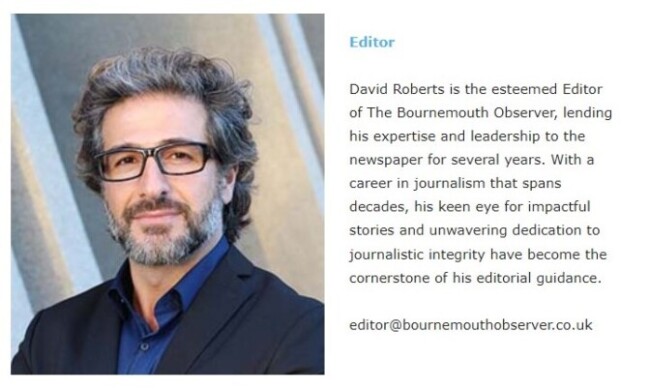

Sharman had been contacted by a ‘Paul Giles’ representing the Bournemouth Observer. On the surface the site looked like your average corporate local news site, dotted with ads and stock-image thumbnails.

But when Sharman made further enquiries about the business, which had only recently launched in June, and its “esteemed” and “seasoned” journalists, he was met with a wall of silence.

Investigating journalists

A small bit of digging revealed that it wasn’t just the stories being illustrated by stock images:

“A ‘Meet the Team’ page on the website, which has now been deleted following our enquiries, listed 11 members of staff with photos and biographies, but we cross-referenced the headshots with an online reverse image search tool and discovered that all 11 pictures were stock images,” Sharman wrote.

Further investigation revealed stories that were either incorrect, or completely fabricated. When cross-referenced with local police records, it turned out that two of the Observer’s crime stories had no police case number.

When pressed, ‘Paul Giles’ responded by discussing the site’s journalistic integrity and the staff makeup of the paper; questions went unanswered. Sharman believed the site to be largely written by AI, as do the many other journalists who have responded to the investigation.

Then, on 6 July, the Bournemouth Observer responded publicly. The awkwardly worded response, written by ‘The Editor’, is a long screed about media bias and the industry’s fear of progress, that claims the site is “polished with the help of AI”.

Defending the site, ‘The Editor’ says that the “Tesco heist”, one of the crime stories that had no police case number, went unreported because the Editor’s wife, who was a witness to the event, could not get through to the police and so “left a voice message; she has had no return call to date.”

Fake news – what’s new?

What’s interesting about this instance of fake news, is that it’s not the ‘fake news’ everyone’s been talking about for the last decade. It’s a new, particular breed of ‘fake news’, one of particular concern to journalists and media nerds (hello).

‘Fake news’, as we’ve come to know it, and as certain politicians have come to throw the term around, is defined by misinformation or disinformation spread by human beings to serve an ideological agenda.

However this fake news is fake because it’s accidentally churned out by a robot that cannot conceptualise the idea of ‘a fact’, understand news values, or make editorial judgements.

The logical next step

It’s important to understand that this isn’t unprecedented. We know why this is happening. Both types of fake news have emerged as specific results of the collapse of journalism’s business model.

The first kind of fake news comes from the fact that, now, pretty much anyone is able to post pretty much anything on social platforms, largely without oversight. This means that conspiracy theorists, for example, can pen convincing posts and blogs and persuade vast swathes of people. (A sub-result of this fakery is that reactionaries, like a certain 45th President of the United States of America, can use this as an argument that you can’t trust anything you see written down, and so you should solely listen to them and their friends.)

The second kind comes from the fact that, in order to wrench back as much advertising revenue as possible from Google and Facebook, the corporate news industry relies ever more heavily on as many sensational articles as possible, for the revenue that comes from each click.

Good journalism takes a lot of human time, hard work, and therefore money. Clickbait does not, and therefore tends to be more lucrative.

So, for the last couple of decades, an increasing number of journalists have had to robotically assemble and publish tweaked press releases, and write inane, irrelevant stories – which has produced the scoffed-at ‘churnalism’ of recent years.

Journalists, being human, are bound to make mistakes – hence the established journalistic processes of right of reply, and published corrections. Journalists expected to produce more than 20 stories a day are essentially guaranteed to make mistakes, write some utter dross, and occasionally breach best practice or even serious ethical standards because they genuinely don’t have the time to go through journalistic processes.

The pros and cons of AI in journalism

I’d argue all journalists have been using AI for a fair amount of time; any spellchecker is a rudimentary AI tool. But in a ‘full-AI journalism’ scenario, where the entire story is produced by a bot, it too is bound to make mistakes – because it doesn’t have the ability to conceptualise what the journalistic process is.

It simply puts one word in front of another according to what it has learned is most plausible, hence why you get ‘phantom’ sources and stories about events that never happened.

This is the logical next step of the cost-cutting, churnalism business model.

But perhaps more importantly, AI also lacks the ability to conceptualise empathy. As it improves, and it will, it is likely to rip away the majority of jobs from the churnalism industry and, if industry trends continue, plenty from reputable newsrooms too. But it’s difficult to imagine a future in which it would be able to entirely replace quality public interest journalism.

By this I mean solid, fact-checked breaking news that avoids sensationalism and, in particular, long-term investigations. Empathy is at the core of both.

So much of investigative journalism comes from relationships between human beings – often one with a conscience, who tips off another that understands how to protect sources, make a judgement on what, and when, to write, and who else to approach to persuasively corroborate a story.

Where a robot will absolutely be able to produce an accurate article based on the transcript of a council meeting, will it ever be able to gain the trust and soothe the fears of several council whistleblowers, sometimes over a number of years, when they’re unsure whether or not to reveal secrets that were never minuted?

Again, this is a business model problem. And so, you’ll have noticed that throughout this page I’ve prompted you to become a member of the Cable.

We are one of the only local investigative media teams in the UK, and one of the few in the world, on a mission to prove that community-owned, ethical and independent investigative journalism can not only survive, but become sustainable.

We can only do this with the financial support of our readers.

Please, if you appreciate the journalistic work we do for Bristol, and the advocacy work we do internationally for ethical journalism, become a member of the Cable today to support our journalism and get member benefits. Thank you!

Report a comment. Comments are moderated according to our Comment Policy.