Road to nowhere: Bristol’s hidden housing crisis

Faced with a unique housing crisis and deep-seated prejudice, where are Bristol’s Gypsy and Traveller population supposed to go?

Photos: Phillipa Klaiber (www.phillipaklaiber.com)

WHY I WROTE THIS

There’s another housing crisis going on, and you probably won’t have heard it because it’s one that only affects Gypsies and Travellers, and they don’t tend to get reported on, unless it’s to complain about an unauthorised encampment. And then the talk is about enforcement and doesn’t touch upon any of the underlying issues. It’s just another case of GRT issues being pushed further and further down the agenda – unless it affects settled people.

Hannah Vickers

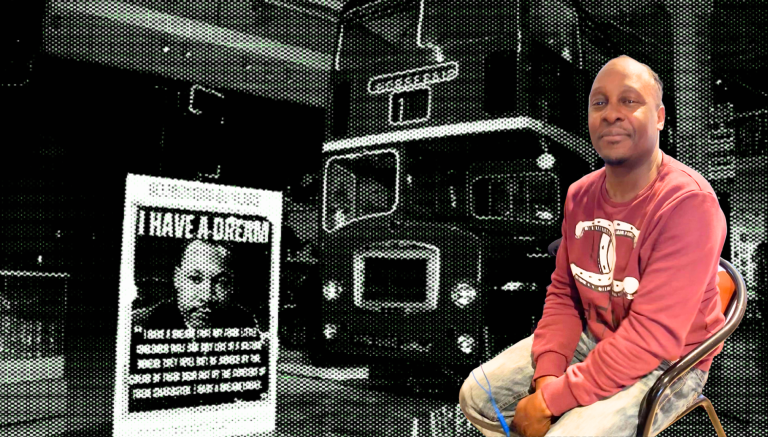

“You know where they’re shoving us? Into bricks and mortar. The simple reason is they want the Travelling and the Gypsy community off the streets, out of their caravans.”

Lynne (not her real name) moved into a house because none of the 12 pitches on Bristol’s only permanent site were available. She hates living in a house. Nobody talks to her and she and her children have had to move three times because of abuse from neighbours.

“My boys are older now but when they were younger they were getting bullied… One of them had a knife up to his neck over being a Gypsy.”

Lynne has had her name down for a pitch for the past nine years; she is one of the many Travellers living unhappily in a house because she can’t find anywhere to live in a caravan.

Marc Willers QC, a barrister specialising in Gypsy, Traveller and Roma law, says forcing Gypsies and Travellers into housing “has dramatic effects on many and causes some of them to suffer mental health problems [such as] depression and anxiety”.

“They often find it difficult to get on with neighbours who can be quite racist towards them, and many end up leaving bricks and mortar accommodation and going back on the road, so it’s a kind of cycle of despair for them.”

“You’re getting a lot of people who are getting depressed,” says Lynne. “I’ve heard of a lot of people dying and getting sick… We live in caravans, we’re used to getting a lot of fresh air.”

According to a 2013 Accommodation Assessment report, living in a caravan near family is an ‘essential part of Gypsy and Traveller culture and wellbeing’. Despite this, councils are reluctant to build sites and the majority of Gypsies and Travellers live in houses.

For Lynne, moving into a house has destroyed her sense of community. “I don’t bother with them, I just go in and lock my door… If I was in a Travelling community, or where my Travelling family is, I’d be out chatting and talking to them.”

The unseen housing crisis

Bristol’s Gypsy, Roma and Traveller (GRT) population consists of Romany English Gypsies, Irish Travellers, Roma, Showpeople and New Travellers. In Bristol, as well as the historic ethnic and cultural Gypsy and Traveller population, a considerable number of people from other backgrounds have also started living in vehicles in recent years.

“Bristol has something larger than just a specific Gypsy and Traveller population to provide for,” says Dr Simon Ruston, a planning consultant working on behalf of Gypsies and Travellers. “There’s also this other large undefined group of people. I would suggest that the council are in a bit of a tricky position trying to meet the needs of all of those groups.”

Around 63,000 identified as Gypsy or Traveller in the 2011 census, the first time the ethnicities were included as options, but there are expected to be many more. The numbers are inaccurate, as many don’t declare their identity because of fear of discrimination. While 359 stated their ethnic group as Gypsy or Traveller in the census, it’s estimated that there are 300,000 GRT living in the UK and that 25% of the South West population live in Bristol.

Only 5% are in caravans, the rest live mainly in conventional housing, and poor accommodation services – including welfare rights advice, tenancy support and site provision – are a key concern for these groups. Gypsies and Travellers are facing a housing crisis that’s going mostly unnoticed by the settled population – apart from when an unauthorised encampment turns up in their local park.

The Site in Weston-super-Mare is flanked on three sides by a cement works, train tracks and scrapyard.

The Site in Weston-super-Mare is flanked on three sides by a cement works, train tracks and scrapyard.Nationally, 16% of caravans are on unauthorised sites – still a tiny percentage of the Gypsy and Traveller population, and unauthorised encampments appear to be on the rise in Bristol and South Gloucestershire. It leads to inevitable tensions with local residents. Charities say it’s because there aren’t enough council sites and getting planning permission for private sites is difficult.

Bristol’s 32 pitches, across one permanent and one transit site, do not meet the need of the local Gypsy and Traveller population. There has only been a 2% increase in socially-rented pitches between 2010 and 2017, which the charity Friends, Families and Travellers says does not account for the natural growth of communities. Lynne agrees, “There need to be more sites in the UK for Travelling people.”

When a site does get built, it tends to be “in the middle of bleeding nowhere”, says Danny Davies-and-Smith. He lives on a council site in Weston-super-Mare, which is close to a motorway and surrounded by a cement works, train tracks and a scrapyard. “They shove us miles away from anything.

“They put us on the land where non-Romanies will not live.

“Why did they put this site here? ‘Cos that’s as far as they want to build houses… they wouldn’t have sold ‘em. Who would walk in here and buy a house next to JCB machinery?

“When they’re driving along, all them machines, this complete site rattles,” he says. “Now who else would put up with that? But if you complain, it doesn’t make a blind bit of difference. Nah, they’re Travellers, they can put up with anything.”

Gypsy and Traveller rights have been steadily stripped away under successive Conservative governments. The Caravan Sites Act 1968, which forced councils to provide sites, was repealed in 1994. The Housing Act 2004 requires councils to assess need and identify potential land for sites, but they aren’t held to actual provision of sites. When each site is so energetically resisted by locals, it’s hard to allocate the much-needed land. New eviction powers were brought in with the Anti-Social Behaviour Act in 2003. And last year, the government re-defined Travellers for planning purposes to exclude those who have permanently settled. “If you stop temporarily you’re ok, if you stop permanently you’re screwed,” explains Ruston.

The definition change has outraged campaigners, who say the government is trying to legislate the race out of existence. Also, it officially reduces the number of Gypsies and Travellers in a local authority and therefore the stated need. Councils across the country are reassessing need so they can reduce the number of sites they have to plan for.

“Generally speaking, councils have used it as an excuse to cut, cut, cut,” says Ruston. Bristol hasn’t redone its needs assessment since 2013-14, so it remains to be seen whether it will use actual or official numbers.

The crackdown

The government has responded to the rise in unauthorised encampments by launching a consultation into increasing enforcement powers – with calls to make trespass a criminal offence – while local authorities across the country are applying for High Court injunctions to ban Travellers from whole areas.

So far, 21 local authorities have got anti-Traveller camp injunctions. In local authorities with an injunction order, anyone staying on council land could be fined, imprisoned or have their property seized if they don’t leave. An injunction makes it easier and faster for a council to evict because it takes away their obligation to conduct welfare checks. It also skews the figures and reduces the accommodation needs of Gypsies and Travellers in a local authority simply by reducing the numbers, allowing a council to avoid making further provision.

Conservative Councillor for Stoke Bishop, John Goulandris, wants Bristol to follow suit. In September last year he failed to persuade the council to get its own injunction and to join the campaign to criminalise ‘deliberate trespass’.

“Technically there is nowhere for anybody to go now is there?” says Davies-and-Smith. “You can’t move onto the side of the road, you can’t move onto a site and you can’t move onto your own land. Where do you live?”

Report a comment. Comments are moderated according to our Comment Policy.

While I know that the majority of Travellers are decent folk, unfortunately there is a minority who leave sites in a dreadful state with rubbish strewn all over the place and in a case near where I live there was even human excrement left on the river bank. It’s a real shame that this minority is what the rest of the public bases their objection to Travellers camping near where they live but sadly this is the case.

Can appreciate how it must be a shock to any traveller who’s lived a life on the road to then end up jammed in like sardines, dealing with bigotry, poor air quality, poor community spirit and the likes. Modern day housing is simply a very unhealthy place to live. Bricks n mortar don’t taste quite like it oughta. It’s a problem waiting to happen and will likely become more pronounced till housing is simply a prison to many. When you’re stuck in it, the alternatives seem few till you reach tipping point then any of them are better.

I recall going to a Bristol council meeting in the 90s

Two possible sites were being considered

One site was on ‘Gypsy Lane’

A man stood up and

said “There is NO EVIDENCE THAT there have ever been travellers PARK UP at GYPSY LANE “…..

I once read a letter by a gypsy which stated that Gypsies who had bought their own land were COMPULSORY PURCHASED

after the 2nd wwar