It’s a gloriously hot June day in Fishponds, the sort that pulls people outdoors to bask in the sun. But for Anela Wood and her husband, who are both blind, days like this can feel more threatening than freeing. The streets of their neighbourhood become a hidden obstacle course—full of dangers that those with sight rarely notice.

I walk with Anela along Manor Road, trying to understand what it means to navigate the world without vision. Her long cane, tipped with a soft ‘tennis ball’ end, sweeps from side to side, helping her locate kerbs, uneven pavements, and trip hazards. But it can’t detect objects at head height—overhanging branches, scaffolding poles, jutting signs. The risks are constant and unpredictable.

These experiences fuel her activism, Anela is a dedicated volunteer with the West of England Sight Loss Council, one of 25 across the UK funded by the Thomas Pocklington Trust. These groups, led by blind and partially sighted people, work directly with organisations to make life more accessible—from transport and health to culture and public spaces.

Her story is a plea for empathy; to redesign our streets with everyone in mind.

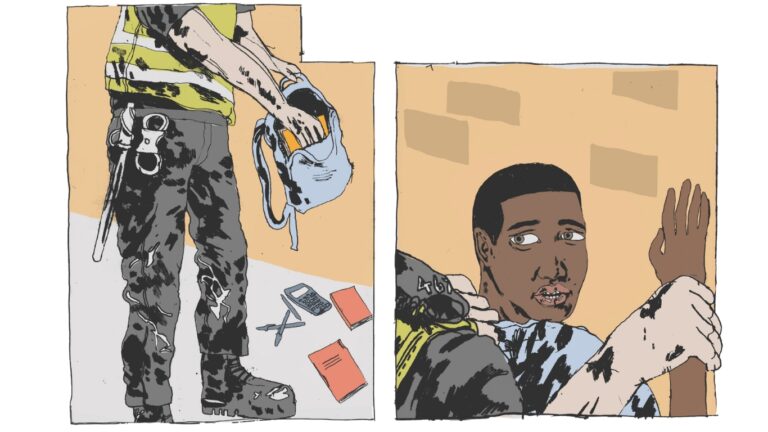

Hidden Hazards

“Sometimes you get a face full of bushes,” Anela says, adding overgrown plants can even force her into the road, swapping one danger for another. Parked cars pose a similar threat, especially those with low bumpers or wing mirrors that jut into her path. “My cane just went underneath that vehicle,” she says. “I could have quite easily walked into it.”

The high street has become more hostile since COVID, with café tables, chairs, and A-boards increasingly cluttering pavements. Anela calls it a constant source of “stress and anxiety” that begins before she even leaves the house. “There’s no such thing as quickly popping to the shops,” she says. “I have to plan around things like bin day and the weather.”

The rise of electric vehicles and e-scooters – quiet by design – presents a new and growing threat. For visually impaired pedestrians who rely on sound cues, this shift is disorienting. “It’s a massive sensory overload,” she says. “You’re trying to listen for cars while avoiding obstacles.”

Each journey becomes a calculation. “Do I step into the road and risk being hit by a car,” she asks, “or stay on the pavement and get hit in the face with something?”

Advocacy in action

Born with congenital glaucoma, she had limited vision as a child—enough to see shapes and colours, but never enough to read or recognise faces. At 11, surgery on one eye went wrong, leading to complete vision loss. At 19, a detached retina in her other eye left her completely blind. Today, she has no light perception at all.

But rather than retreat, Anela has become a campaigner, with the West of England Sight Loss Council. A standout campaign is “Cut It Back,” which pushes councils and residents to tackle overhanging foliage that encroaches on pavements.

Another tool is the “sim spec walk,” where decision-makers wear simulation glasses to get a sense of what it’s like to navigate the city without sight. “After a sim spec walk, they really understand the issues,” says Yahya Pandor, Engagement Manager for the Sight Loss Councils in the Southwest in comments to the Cable. “But long-term change? That’s where they fall short.”

Persistence is essential, Anela adds. “If you don’t stay on their back, things go back to normal.” In places like Manor Road, where street clutter has only increased since the pandemic, the barriers can feel endless.

“We’re not just complaining—we’re offering solutions,” she adds. “We want to help build a city that works for everyone.”

Through the lens of empathy

Yahya puts it simply: “Look at the world through the lens of empathy.” Streets aren’t just for people with perfect sight or steady footing. Accessibility also affects wheelchair users, people with mobility aids, older people, and parents with prams. Small choices—parking on pavements, leaving bins out, letting hedges grow wild—can have outsized consequences for others.

Anela’s message to the people of Bristol is clear and practical: “Cut back your foliage. Don’t leave it hanging into the street.” Her plea to the authorities is for follow-through and consistency—not one-off gestures but sustained attention.

Her advice for interacting with someone using a cane is equally simple: “Ask, don’t assume.” A quick “Excuse me, are you okay?” is far better than grabbing someone unexpectedly. “I’m blind, not deaf,” she says, dryly.

Bristol is becoming harder to navigate, Anela observes. More cars, more scooters, more clutter. But she believes change is possible. With enough voices, enough pressure, and enough empathy, streets can be designed with everyone in mind.

As someone who is disabled, I feel Anela’s frustrations in my own body. I walk with a stick; she walks with a cane. Mine helps me stay upright. Hers reaches forward, reading the world as she moves through it. I recognise that blend of caution and determination, the need to plan even the simplest trip. And I understand the weariness that comes from navigating spaces not made with us in mind.

What Anela shows is that this isn’t just about one person’s struggle—it’s about a city’s priorities. Accessibility is not a favour. It’s a right. And it starts by looking again at the streets we thought we knew, and seeing them not just through our own eyes—but through hers.

Tell your friends…

Independent. Investigative. Indispensable.

Investigative journalism strengthens democracy – it’s a necessity, not a luxury.

The Cable is Bristol’s independent, investigative newsroom. Owned and steered by more than 2,600 members, we produce award-winning journalism that digs deep into what’s happening in Bristol.

We are on a mission to become sustainable, and to do that we need more members. Will you help us get there?

Join the Cable today

Report a comment. Comments are moderated according to our Comment Policy.

I so agree, Bristol’s pavements have become really difficult, if not downright dangerous for anyone with, even slight, impairment. I have severe balance issues that require my walking with a stick. To maximise my core strength my GP have referred me to Horfield Leisure Centre for some regular gym exercises. The Centre’s car park boundary hedge has been allowed to take up half the width of the very narrow pavement of Dorian Road: a link road between Southmead Hospital and the A38 so busy with ambulances, delivery vans and lorries, double-decker buses and private vehicles. Ironic that EveryoneActive gives customers’ cars greater security than those of us who walk and bus to their facility who include NHS patients with various disabilities as well as parents with toddlers in pushchairs using the swimming pool.