Private probation companies are sending more people to jail. But not for committing crimes

Outsourced providers in the Bristol area are under heavy fire for sucking up millions in public money, but failing on public safety and criminal justice.

Maria da Silva is a trainee on the Bristol Cable Media Lab 2018.

Illustration: Rosie Carmichael

Many will have missed it – but probation services across the country were partially privatised in February 2015. Fast forward three years – these services are now facing heavy criticism on several fronts.

Ian Lawrence, the General Secretary of the National Association of Probation Officers has told the Cable that probation workers are “feeling worried about the service delivery”.

The concerns have come about since partial privatisation saw the management of medium to low risk offenders on probation transferred to 21 private ‘Community Rehabilitation Companies’ (CRCs). High risk offenders continue to be managed by the National Probation Service.

The CRC for BristoI, Swindon, Wiltshire & Gloucestershire is Working Links. In 2012 the company’s former chief financial auditor alleged a “multi-billion pound fraud” in the form of falsifying records to meet government targets on getting unemployed people back into work. The company denied the allegations and the government ruled that no further action would be taken.

Now owned by a German investment firm, Working Links’ reputation in probation services also appears less than unblemished. The August 2017 inspection of Working Link’s services in Gloucestershire led the Chief Inspector of Probation to say that “there have been drastic staff cuts to try and balance the books. Those remaining are under mounting pressure and carrying unacceptable workloads that prevent them doing a good job”.

In contrast, the Chief Inspector found that the public National Probation Service was “performing reasonably well” and called for Working Links and the government to “to work together urgently to improve matters”.

So what exactly needs addressing ‘urgently’ and what are probation workers feeling ‘worried’ about?

People sent back to prison, but not for committing new crimes

There are multiple reasons for probation workers to ‘recall’ someone back into prison. However the non-crime categories of ‘Failure to keep in touch’ and ‘Non compliance’ have outpaced reoffending as reasons to be sent back to prison since Working Links began delivering the contract in the Bristol region.

Figures obtained by the Cable show that since the beginning of the contract, non-crime related offences that resulted in returning to jail, such as failing to stay in touch with the probation officer had doubled.

Over the two and a half years that data is available, only one in four of recorded reasons for sending people back to jail were related to further criminal charges.

Andrew Neilson, director of campaigns for the Howard League for Penal Reform, said that “being recalled back into custody for technical breaches like missing appointments is something that should really be the exception not the norm. Seeing this as a failure of the system rather than the individual would be a much fairer and more accurate presentation of what’s actually happening”.

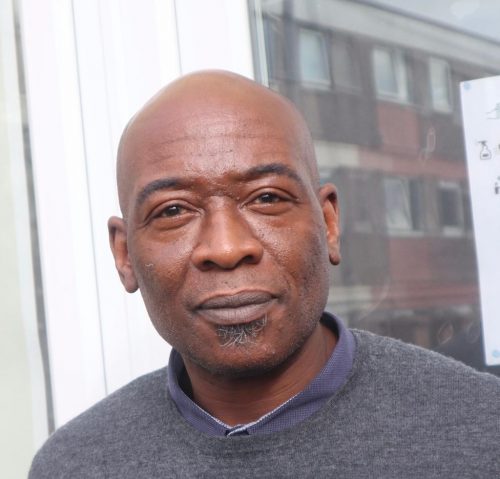

A human face for this system failure is Danny (not his real name). Recently on probation with Working Links in Bristol, Danny told the Cable that although he went to see his probation worker every month, they provided no additional support or signposting and the “meetings generally felt like a tick boxing exercise”. He says he was lucky to already be linked into services that could support him or otherwise he’d be falling between the gaps and back in the prison system.

Staff Cuts, unmanageable caseloads and ‘best practice eroded’

Massive cuts to staffing levels in privatised services have prompted concerns that probation workers cannot engage with re-offenders sufficiently. This in turn leads to a breach of their probation terms and a return to prison, despite them having committed no crime.

The probation worker’s trade union, the National Association of Probation Officers (NAPO) told the parliamentary Justice Committee inquiry that a 20-month dispute with Working Links has its origins in a “decision to reduce staffing provision by some 50% in the first year of the contract”.

A probation worker in the Bristol region said: “Working Links prioritises meeting targets over risk management. Management are not responding to my concerns and I feel deflated as my workload is not manageable.”

The impact of such cuts in Gloucestershire was confirmed by the Chief Inspector who highlighted that “caseloads have increased exceptionally, with Probation Officers carrying 75 cases and Probation Service Officers over 90 cases.”

The Chief Inspector’s report goes on to say that Working Links “had lost contact with the offender for significant periods” and “offenders were not being seen often enough. As a result, the public were more at risk than necessary, and offenders who could turn their lives around were being denied the chance to do so.”

Neilson of the Howard League says that “one of the most depressing things about people being recalled in response to the failing of the probation system – it’s not the contracts that companies have that are being recalled, it’s the people that they deal with that are being recalled. In many cases these are people that have been set up to fail but the expectations placed on them, by a system that can’t support them through those expectations”.

Responding to these issues a spokesperson for the Working Links said “we welcomed HMIP’s report into our work in Gloucestershire last year, which has highlighted many pieces of good practice as we work hard to combat re-offending”.

The prison – probation roundabout

In an attempt to reduce reoffending, the Conservative-led coalition introduced the Offender Rehabilitation Act 2014. However, Neilson highlights how the increases in recalls to prison by the private companies charged with the task run against the government’s rehabilitation goals. “Many people are recalled for only 14 or 28 days before being released from prison on license again. This is barely time to complete their induction to the prison, but long enough to put homes and jobs at risk and disrupt relationships with their families and other agencies.”

“People on short prison sentences are some of the most vulnerable people in the system, often leading particularly chaotic lives and facing multiple challenges. Unless they are properly supported, we are likely to see recall rates continue to rise”. This will likely result in less safety for the public, stubbornly high re-offending rates and p the UK continuing to be at the top of the table for imprisonment in Western Europe.

What next for probation services?

It the midst of all this criticism, what does the future of probation services look like? Neilson believes privatisation has failed.

“When you’re dealing with creating a market and privatising services that work with people who often lead very chaotic lives it’s just going to be very difficult to do and so it has proven. It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that privatisation was not really about the ‘rehabilitation revolution’ and payment by results, but actually about saving money.”

Despite indications that privatisation wasn’t delivering the results, in July 2017 the government awarded struggling CRCs with an extra £342 million of taxpayers’ money, with Working Links being awarded £4.3 million. The parliamentary body that scrutinises public spending, the Public Accounts Committee was not impressed, pointing out that the Ministry of Justice “could not explain what it is getting back for this extra commitment and despite this bailout, 14 out of 21 CRCs are still forecasting losses”. The committee also said that the “The Ministry still does not have complete and robust performance information, creating a risk that CRCs are not being held to account”.

The question of short-term savings and long-term costs due to rising prison numbers and re-offending has led the The National Association of Probation Officers to conduct research into the re-nationalisation of probation services. They found that the government would actually save money if services returned to public ownership.

However, it won’t be easy to address any issues before the end of the contract in 2022. According to Neilson, “the government would have to pay an awful lot of money” because of clauses in the privatisation contracts that obstruct early termination. For a party that both wants to shrink the public sector but be tough on crime, “this has come to haunt the Conservatives”.