No silver bullet: why we should stop criminalising young people and start investing in them

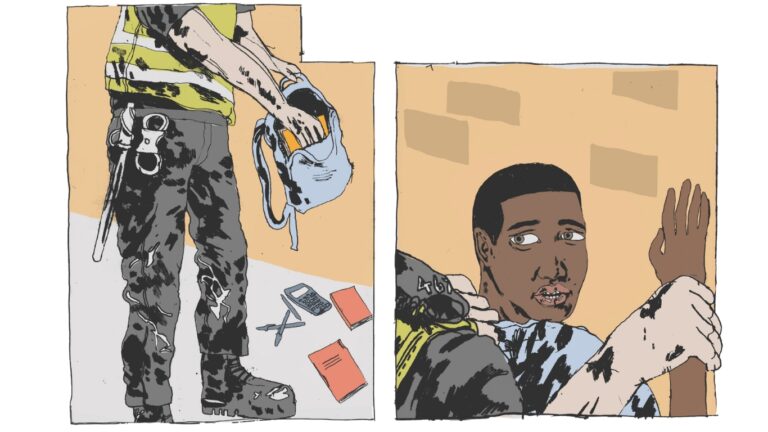

credit: @alexcarlturner

Clare Moody, the police and crime commissioner for Avon and Somerset, makes careful notes as she hears from the audience at one of her public consultation events. Moody nods and looks concerned, as people rattle off their views on the state of policing in Bristol and their ideas for what the force’s priorities should be going forward.

The venue is the entire first floor of Sparks Bristol department store in the city centre. It’s far too large for the two dozen or so people who have turned up, the majority of them local Labour politicians who campaigned alongside Moody, police officers or members of organisations that work closely with them.

Reducing serious youth violence is a priority area for Moody as she works on her police and crime plan for her term to 2029, as it is for many across the city. The issue was again thrown into the spotlight last year after three teenage boys lost their lives in fatal stabbings over the space of 18 days at the end of January and into February 2024.

But finding solutions to knife and youth violence in Bristol is a task that doesn’t lie squarely in the remit of policing. Instead, Moody, like the region’s chief constable Sarah Crew, acknowledges that a so-called multi-agency approach that addresses the underlying causes of it is needed to tackle the problem.

This more holistic approach, in theory, should empower other public and community services like youth charities to not just have a say, but play an active role in the prevention of crime. The Cable spoke to signatories of the Together for Change campaign [see box-out] about what this should look like, and if the police are even listening.

Possession is not the key issue

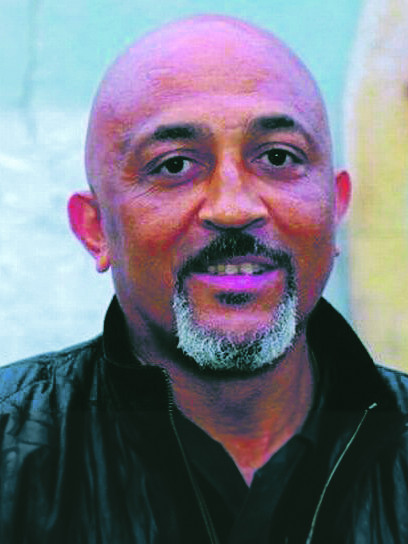

“Of course we don’t want young people to be carrying knives, but that isn’t the issue,” says Desmond Brown, founder and CEO of Growing Futures, an organisation that works with children, young people and their families, who have been impacted by school exclusions, serious violence or child exploitation.

“They are carrying them not because they’re the perpetrators, but because they are afraid of being stabbed,” Brown adds. “Our children don’t feel protected by their parents, the police, their school or the city, and they feel that they have to protect themselves. I’ve seen young people picked up off the street because they are carrying weapons, and to criminalise them means that they will become the perpetrators going forward – they will lose hope in society.”

“As the police often say, we’re not going to enforce our way out of the situation,” says Brown, who has long worked closely with the police on the issue, and with other organisations and institutions like the city council.

He points to the police’s increased use of Section 60, which gives officers the power to stop and search people without suspicion that they have committed a crime, in the aftermath of knife and youth violence. Use of the power often results in racist over policing.

During a Section 60 operation in February, following the murder of 16-year-old Darrian Williams in Easton, officers searched children as young as 10, found no knives, and disproportionately targeted people of colour. (Turn to the opinion pages to learn more the Cable’s campaign to stop the use of this racist, ineffective and completely unnecessary tool).

A hyperlocal approach

“Young people listen to those who are in their immediacy – in their neighbourhood,” says Martin Bisp, co-founder and CEO of Empire Fighting Chance, a youth charity and boxing club based in Easton.

“We need to make sure that those who are most trusted by these young people are empowered and funded to help prevent and reduce violence.”

“If you reduce money going into areas where you’re going to engage young people then… you start to see problems, and inevitably you’re reducing all the things that we need to invest in in order to make long-term change,” adds Bisp.

“It’s possible and we’ve seen it done in cities elsewhere in the world,” he says, pointing to Medellin, Colombia, which was the murder capital of the world in 1991, with 16 people killed there every day.

Since then, the city has invested in urban infrastructure projects, as well as boosting police, health and social services in rural areas of extreme deprivation, helping to cut its homicide and poverty rates dramatically.

School to prison pipeline

Leanne Reynolds is a campaigner on the issue of knife violence and fundraised for ‘bleed kits’ to be installed across Bristol. She held a vigil in Knowle West for two boys, Max Dixon and Mason Rist, aged 16 and 15, who were fatally stabbed in February.

“When we have a fatality, we find that things are happening quickly… There’s a police investigation, but then they leave and children and communities are left traumatised, but the police didn’t even think about… the trauma that has been left behind,” she says.

She says there are safe spaces for young people in the city but that they need a funding boost. This is also the view of the National Education Union, whose representatives told a summit earlier this year that cuts to youth services have led to an increase in violence among young people.

School exclusions are also blamed by some, which is an issue on the rise in the city. In 2023, more than twice as many Bristol school children were permanently excluded compared to the previous two years. Exclusions disproportionately impact those from Black and minority ethnic backgrounds and working-class communities.

But with schools struggling to support their students, not everyone agrees that simply banning the practice of school exclusions – seen as a driver of the so-called ‘school-to-prison-pipeline’ is an answer.

Bisp, whose charity and boxing gym works with children who have been excluded from school, says the conversation around the issue needs to be more “nuanced”.

‘Stop victim-blaming young people’

Early intervention is also key. That’s something crime commissioner Clare Moody spoke about the need for at her consultation events – focusing on “understanding and changing behaviour”.

But however true that is, the police continue to criminalise innocent young people.

Eight out of 20 people stopped more than 20 times by Avon and Somerset police officers over the last seven years were between the ages of 10-17 years old, according to unpublished data seen by the Cable.

And just over 70% of strip searches on children – the most intrusive stop-and-search power the police have at their disposal – resulted in either no further action or ‘no recorded outcome’. The arrest rate was 18%, with only one of the 17 full strip searches on children resulting in an item being found.

Brown, who has long worked closely with the police on the issue of tackling serious youth violence, says there isn’t a “silver bullet” when it comes to solutions on the issue.

“We need to talk about medium- to long-term solutions,” he says, “and move away from victim-blaming [young people] for the society they have been born into.”

Independent. Investigative. Indispensable.

Investigative journalism strengthens democracy – it’s a necessity, not a luxury.

The Cable is Bristol’s independent, investigative newsroom. Owned and steered by more than 2,500 members, we produce award-winning journalism that digs deep into what’s happening in Bristol.

We are on a mission to become sustainable, and to do that we need more members. Will you help us get there?

Join the Cable today