Local mental health trust misses deadline to stop sending people far away from home, data shows

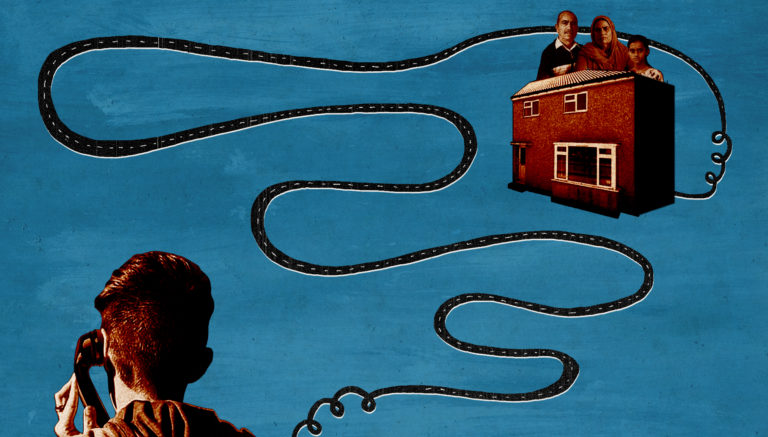

Illustration: Rosie Carmichael

Illustration: Rosie Carmicheal

Bristol’s local mental health trust is still sending people miles from home for treatment, meaning they have failed to meet their target of ending ‘Out of Area Placements’ (OAPs) caused by local bed shortages. An inappropriate OAP is when someone is sent to a bed outside of their local mental health trust because there aren’t any beds available locally.

Latest NHS data released on Thursday (10 June) showed that Avon and Wiltshire Mental Health Partnership Trust (AWP) had 30 active inappropriate OAPs as of March 2021. This was down to Covid-19 reducing bed capacity because of infection control measures, AWP said.

It means the trust has missed the key national deadline of eliminating inappropriate OAPs by the end of March 2021. Nationally, only 15 out of 55 NHS Trusts managed to meet the target.

“It can have a devastating impact on patients and their loved ones. Treating patients close to home speeds up recovery, reduces the risk of suicide and shortens hospital stays”

Last year, Cable analysis of NHS data revealed a near 20% increase in inappropriate OAPs under AWP in 2019, from 325 to 385 placements, compared to the year before. Now, analysis of 2020 NHS data shows a reduction of 17%, from 385 to 320, compared to the previous year, bringing levels back down to those seen in 2018.

But in the same period, the cost of inappropriate OAPs increased from £4.4m to £5m and the average stay from 23 days to 27 days. These are figures for adults only, as OAP data for children is not publicly available.

Meanwhile, patients continue to be sent far away from home to often private hospitals, run predominantly by The Priory Group and Cygnet Health Care, who are paid millions annually to deliver NHS mental health services.

Amid underfunding, mental health charities and organisations say the NHS cannot be left carrying the can any longer, and are calling for “urgent action” to break the “cycle of treating crises rather than preventing them”.

A ‘challenging’ year

Before the pandemic, AWP “made good progress” towards reaching the March 2021 goal, Matthew Page, AWP’s chief operating officer, told the Cable.

“As we begin to emerge from the pandemic, many of the challenges we have faced, including a reduction in the number of beds due to needing to maintain high standards of infection prevention control, remain in place, meaning the situation continues to be challenging.”

AWP was operating at 95-100% bed capacity in 2019 according to the latest available CQC inspection. As a result of bed shortages, the then 21-year-old young mother-to-be Safia* was sent 100 miles away to Priory Hospital Woking in Surrey before being sent to Cygnet Hospital Beckton in East London in February last year. She described her stay at the secure unit at Beckton as “the scariest place she’s been to”.

Nationally, the number of NHS beds has fallen in the last ten years, in part in an attempt to treat more people in the community. But with supply and demand unpredictable, private hospitals provide “a short term solution […] to spikes in demand which we’re unable to immediately respond to,” AWP told the Cable last year.

Despite the missed deadline, AWP remains “committed” to eliminating OAPs, Page said. “We know our patients have a better experience and respond more effectively to treatment when closer to home and their support networks.

“We are working closely with our commissioners on our improvement plan, which includes investment in our community mental health, crisis and home treatment and street triage teams to ensure people get access to mental health expertise at the earliest opportunity to prevent the need for admission.”

‘Urgent action’ needed after ‘stalled progress’

“It is extremely disappointing that progress towards eliminating inappropriate out of area placements has stalled,” said Dr Adrian James, the President of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, in response to the latest figures.

He called for “urgent action to ensure that local mental health beds are readily available for all patients that need them”, describing the practice as “unacceptable”.

“It can have a devastating impact on patients and their loved ones,” he said. “Treating patients close to home speeds up recovery, reduces the risk of suicide and shortens hospital stays.”

Chief executive of Rethink Mental Illness Mark Winstanley described the latest figures as “incredibly disappointing”, adding that OAPs come “at huge financial cost to the NHS and personal cost to individuals.”

“It doesn’t surprise me that there are currently 30 OAPs. It really doesn’t at all. I know of three,” said Rachel Barclay, founder of 2 Way St, a self-funded organisation supporting parents and carers with children in the mental health system.

Rachel set up 2 Way St after the lack of support she felt over the years with her son who has been on several OAPs from Weston-Super-Mare to Essex.

“The [mental health] system isn’t built up to be proactive or preventative, it waits for it to get in crisis and we don’t have the spaces here in Bristol, we physically don’t,” Rachel said.

Covid-19 has only exacerbated pre-existing problems as people struggled with remote contact and new systems, explained Rachel, who has been actively supporting at least 15 families during the pandemic.

She called for more focus on early intervention and investment in crisis houses so that people get support before they reach crisis point.

Mark Winstanley urged the government to “wake up to the pressing reality that progress on this issue is only ever going to be made once sustainable funding has been put in place for mental health social care”.

“The NHS has been left carrying the can. Without investment in appropriate step up and step down services and wider support to enable people to thrive independently in their communities, mental health needs escalate and those affected will continue to be sent miles away for expensive inpatient treatment.

“We have to break the ongoing cycle of treating crises rather than preventing them. This can only be achieved by investing sustainably in mental health social care.”

Report a comment. Comments are moderated according to our Comment Policy.